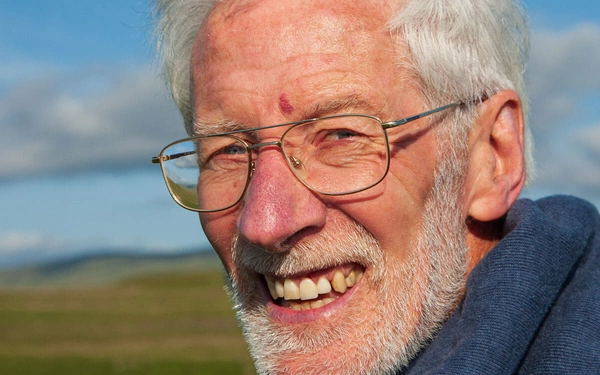

Kev Reynolds: A tribute

Kev Reynolds, one of the country’s leading outdoor writers, died on Friday 10 December 2021, three days after his 78th birthday.

‘What does Kev say?’

Kev was a leading Pyrenean expert, admired across the world. He knew the Alps from end to end as few do and explored Nepal and the Himalaya over the course of 20 extended trips. He also had extensive knowledge of Kent, where he made his home, and southern England.

Kev wrote over 50 books, mainly guides and inspirational titles to his much-loved mountains, and became a master-craftsman of this unlikely but challenging art. He said it was ‘the best job in the world’ and quickly became a leading practitioner with his guides published by Cicerone for whom he became a leading writer and counsellor.

He was a lifetime and then honorary member of a range of organisations including the British Association of Mountain Leaders and Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild, whose lifetime achievement award he received in 2014. His work was widely recognised by his peers. He became a skilled lecturer, giving up to 50 talks each winter.

As well as his exploring, writing and talks, Kev was a devoted family man. His life-long love Min enabled his many adventures and they brought up their two daughters Claudia and Ilsa during a full life running a youth hostel before Kev became a full-time writer.

Kev was born in 1943 at Ingatstone in Essex and remained a proud Essex man his whole life. After school, where he received the traditional ‘you won’t amount to much’ treatment so redolent of the Britain of the 1950s and 60s, he was directed into local government. It was an unlikely stroke of luck. It is unclear whether it was the detailed and tedious nature of the work, the boredom of it all, the need to escape, or all of these, but 1960s local government became an incubator of outdoor writers, their gaze turned from the grey functional buildings to the green rolling world outside.

Weekends, when not courting Min, were spent getting away from the flat lands to the hills and mountains of the Lake District, Snowdonia, and Scotland. He thrived, and became a strong and safe mountaineer.

A first trip to Morocco in 1965 was Kev’s first adventure abroad. Four lads from the Nansen Club in Hereford in an old truck, with France and Spain to cross before getting to the Atlas Mountains was an education in its own right – 1960s Spain was starting to awaken from its long slumber, whilst Morocco was a blaze of colour and scent and difference.

In was in Morocco that he told friend Mike that when he came home, he was going to pack in the job, seek employment outdoors and propose to Min. Mike’s reply was ‘Are you mad?’

Undaunted, Kev married Min in 1967, and the young couple escaped the tedium of local government to work in a hostel in St Moritz. The pay was negligible, but the mountains on the doorstep (and a lift pass) offered an escape as they explored the nooks and crannies of the beautiful Engadine region in eastern Switzerland. They became skiers as well as alpine walkers and climbers.

Returning to the UK, they took on a Youth Hostel in Crockham Hill in Kent close to the Downs. Life was busy – running the hostel, dealing with the hostellers, bringing up the family, and escaping to the mountains. Then as now the YHA was a financially frugal organisation, so Kev recognised the need to develop a second career.

Always a storyteller, could Kev translate his passion for adventure into written words? Even better, words that generated an income? Starting with articles in magazines and contributions to books, Kev struck up a relationship with legendary outdoor magazine editor Walt Unsworth at Climber and Rambler magazine. The breakthrough came in 1976, when Walt, famous for his slightly gruff but kindly development of authors, suggested that Kev expand his Pyrenean articles into a full book for Cicerone, the publisher that Walt had launched a few years previously with partner Brian Evans and their families.

It was a stern apprenticeship. The Pyrenees are big and writing is hard. Guidebook writing at its best needs a deep understanding of the region, the ability to select desirable routes and areas. It needs writing skills, cartographic, photographic, and now digital skills too. Authors need to become part geologist, part botanist, safety expert, historian, and interpreter; they need to master languages, transport schedules and many other things, all before starting to type. It needs the ability to inspire whilst often dealing with seemingly dry material on routes and planning information. It’s tougher than it looks. As Walt would say, ‘It’s a hard job, but someone has to do it,’ alluding to the pleasures of getting it just right.

But it gradually all came together. The result was the first edition of Walks and Climbs in the Pyrenees, first published in 1978 and still in print in its seventh edition today. It remains a classic guide to Europe’s last wilderness. It caught the attention of the Ravier brothers, famous Pyrenean climbers and explorers, and was the beginning of one of many long friendships with writers and climbers worldwide.

Other guides followed. Switzerland was an obvious target. Guides to the Engadine, Bernese Alps, Valais region and Ticino came steadily, as did the establishment of the Walkers’ Haute Route from Chamonix to Zermatt and the Tour of the Jungfrau. The French Alps too, with guides to the Écrins and Vanoise ranges and treks around them. Kev took forward the guide to the well-known Tour of Mont Blanc when author Andrew Harper died.

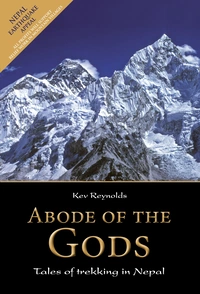

Kev’s first trip to Nepal and the Himalayas was in 1989, a trek to Kangchenjunga. Over the next 30 years, Kev made nearly 20 trips to Nepal and bordering areas in India. These included long exploratory trips into Dolpo and western Nepal long before they opened for trekkers, days without maps and sometimes food. Kev struck up a deep friendship with Kirken Sherpa, and they made many of these trips together. Min too became a Himalayan trekker, joining Kev on many trips. The books naturally followed – guides to Annapurna, Everest, Kangchenjunga, and Manaslu which Kev regarded as ‘the most beautiful walk in the world’.

England is a beautiful country too. Kev and Min had left the hostel and trusted that the writing would work out. They settled nearby in Crockham Hill and later Edenbridge, close to the Downs, and were keen supporters of the local church and community. Kev turned to the local hills, small in comparison with the Alps but still providing great walking. Guides came to the North and South Downs Ways, Kent, Sussex and, when it opened in 2010, the South Downs National Park and a rare venture north of London onto the Cotswold Way.

But guidebooks are like a garden, they need continual weeding, pruning and re-potting. They require continual revisiting and updating, checking routes and finding new ones, to nurture them through reprints and new editions over the years. This labour of love extends through the lifetime of a guide, providing ample excuses (as though any are necessary!) to revisit favourite areas and routes.

More ambitious projects followed. Walking in the Alps is a complete survey of all the best walking across Europe’s main mountain range. Detailed books on the Pyrenees and Swiss Alps for mountaineers, walkers and trekkers were a major challenge. And more recently reminiscences of expeditions in Nepal – Abode of the Gods – and European mountains – A Walk in the Clouds – allowed Kev to reflect on a lifetime of exploration.

Kev and Cicerone had formed an unbreakable connection over decades, so when Cicerone’s fiftieth anniversary approached, Kev gladly took on the orchestration of a book celebrating Cicerone’s fifty years of publishing. Working with Cicerone authors, editors and designers he assembled a celebration of all that is best about Cicerone’s writing and our mission to inspire adventurers in Fifty Years of Adventure.

Walt had retired in 1999 when Jonathan and Lesley Williams bought Cicerone from the founding families. A new friendship was struck between publisher and author and Jonathan and Kev became firm friends as well as colleagues. Kev’s counsel was highly valued, and they made many trips together. Jonathan will relate some of these in some personal notes but be prepared for ‘the one where they fight over a Nepalese toilet’ and ‘the one where they spend the day in a green plastic bag’, ‘the one where they sit in an Italian railway station and list all the books they want to make’ as well as ‘the one where Kev snoozes on a rock all afternoon while Jonathan rushes around the mountain’.

The relationships were not just with Jonathan and Lesley, but with the whole Cicerone team. Kev worked hand in glove with Cicerone’s small team of editors, designers and marketers. Every new book was greeted with incredibly courteous, delightful, effusive personal letters of thanks. Making books is hard work, but this was a joy. Designer Clare Crooke became especially close in recent years, but we all have our own stories.

These are the bare facts, but what about Kev the man? He was kindly and positive in all his relationships. It’s hard to believe that he ever lost a friend and he made them throughout his life in the mountains on every trek and trail. Many Cicerone readers came to know him personally. Above all he was a devoted and loving husband to Min and father to Claudia and Ilsa and relished being grandfather to Charlie and Billy. His and Min’s collection of friends from the local villages and towns was extensive.

He was a fine writer and photographer, but became, if such is possible, an even better talker, giving many, many slide shows to enthusiasts and those merely interested.

But most of all he retained his honest modesty. He used to relate the story of walking in the company of several groups of trekkers for a few days, sitting quietly in the huts and assembling his notes, photos, and thoughts every night, trying to travel incognito. Eventually one of the trekkers took him aside on the trail and said ‘you are like Henry the Fifth on the night before Agincourt’ as he unmasked the reticent writer. It was an occupational hazard that despite the loss of solitude, he loved, as it brought new friends.

The trekkers are sitting outside the hut, waiting for sunset and dinner, quietly drinking their beers. Gradually they start to think about the next day, the cols to cross and peaks to climb on the route. Someone asks, ‘what does Kev say?’ and the trekkers bring out their blue guidebooks to the route and study them again as they have done for months and days before.

What does Kev say? – quite a lot, really.

Jonathan Williams

Cicerone

For Kev’s online remembrance book see Kev Reynolds | Online Condolence Book (rememberancebook.net)

For a listing of Kev’s books, see Kev Reynolds | Cicerone Press

For a listing of Kev’s articles and other contributions to Cicerone’s site, see Kev Reynolds: Remembering the man with the world's best job.